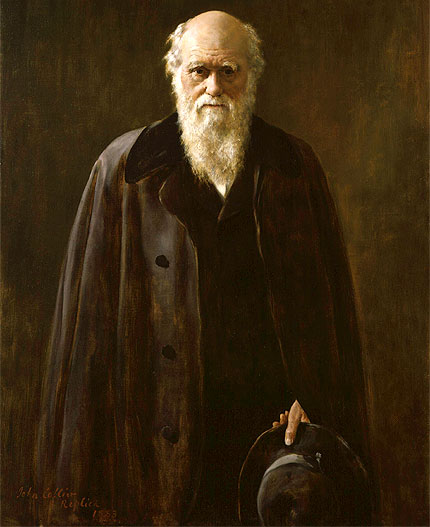

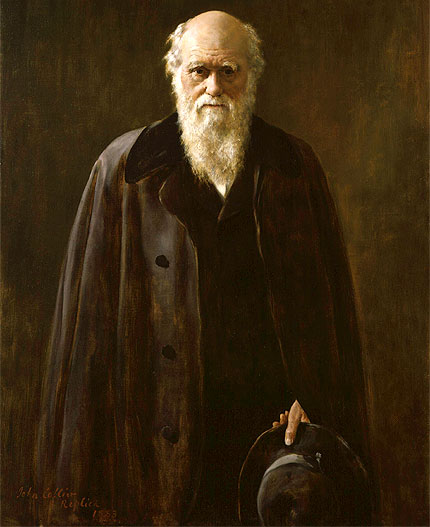

Darwin en la época del Diario del Beagle

(Fragmentos del Diario de viaje de Darwin)

Todos los aborígenes han sido trasladados hasta una isla en el estrecho de Bass, de modo que el País de Van Diemen disfruta de la gran ventaja de estar libre de la población nativa. Este paso tan cruel pareciera haber sido prácticamente inevitable, en términos de detener la temible sucesión de robos, incendios y asesinatos cometidos por los negros, pero que tarde o temprano deberían concluir en su extrema destrucción. (...) El plan adoptado (para exterminarlos) era cercanamente parecido al de las grandes partidas de caza en la India: se formó una línea que cruzaría a lo largo de la isla, con la intención de llevar a los nativos a un callejón sin salida en la península de Tasmania.

All the aboriginals have been removed to an island in Bass's Straits, so that Van Diemen's Land enjoys the great advantage of being free from a native population. This most cruel step seems to have been quite unavoidable, as the only means of stopping a fearful succession of robberies, burnings, and murders, committed by the blacks; but which sooner or later must have ended in their utter destruction. I fear there is no doubt that this train of evil and its consequences, originated in the infamous conduct of some of our countrymen. Thirty years is a short period, in which to have banished the last aboriginal from his native island,—and that island nearly as large as Ireland. I do not know a more striking instance of the comparative rate of increase of a civilized over a savage people.

The correspondence to show the necessity of this step, which took place between the government at home and that of Van Diemen's Land, is very interesting: it is published in an appendix to Bischoff's History of Van Diemen's Land. Although numbers of natives were shot and taken prisoners in the skirmishing which was going on at intervals for several years; nothing seems fully to have impressed them with the idea of our overwhelming power, until the whole island, in 1830, was put under martial law, and by proclamation the whole population desired to assist in one great attempt to secure the entire race. The plan adopted was nearly similar to that of the great hunting-matches in India: a line reaching across the island was formed, with the intention of driving the natives into a cul-de-sac on Tasman's peninsula. The attempt failed; the natives, having tied up their dogs, stole during one night through the lines. This is far from surprising, when their practised senses, and accustomed manner of crawling after wild animals is considered. I have been assured that they can conceal themselves on almost bare ground, in a manner which until witnessed is scarcely credible. The country is every where scattered over with blackened stumps, and the dusky natives are easily mistaken for these objects. I have heard of a trial between a party of Englishmen and a native who stood in full view on the side of a bare hill. If the Englishmen closed their eyes for scarcely more than a second, he would squat down, and then they were never able to distinguish the man from the surrounding stumps. But to return to the hunting-match; the natives understanding this kind of warfare, were terribly alarmed, for they at once perceived the power and numbers of the whites. Shortly afterwards a party of thirteen belonging to two tribes came in; and, conscious of their unprotected condition, delivered themselves up in despair. Subsequently by the intrepid exertions of Mr Robinson, an active and benevolent man, who fearlessly visited by himself the most hostile of the natives, the whole were induced to act in a similar manner. They were then removed to Gun Carriage Island, where food and clothes were provided them. I fear from what I heard at Hobart Town, that they are very far from being contented: some even think the race will soon become extinct.

N.B.-Las palabras destacadas en negrita corresponden a la lectura de Lisarda.

5 comentarios:

La destrucción de pueblos enteros por medio de la "civilización" es una constante en la historia, y no tenemosque ir hasta Tasmania para verlo, aqui en américa hay innumeros ejemplos de ello.

Las venas abiertas de América Latina dan testimonio.

Un abrazo

Vou checar se consigo a tradução deste livro para o português.

Gregorio, es verdad que tenemos ejemplos por casa y que en todas las épocas ocurrieron masacres.Creo, sin embargo, que hay una diferencia cualitativa en este detalle:en que a partir del siglo XIX las masacres se justifican desde el discurso científico. Desde la supervivencia del más apto pasando por la eugenesia,el nazismo,y el calentamiento global, abundan ejemplos de extrapolación jurídico-moral a partir de datos brindados por las ciencias naturales y sociales.

La justificación científica ha reemplazado a la justificación religiosa: así como en el siglo XVI era impensable discutir la preeminencia del cristianismo sobre los idólatras, ahora abstracciones como "lo global" o "la hunanidad" están por encima de los pueblos originarios. La transculturación se justifica por las nuevas posibilidades laborales que brinda el turismo.

Así, con términos abstractamente positivos más la petición de principio de que sean indiscutibles, así es como se cometen los etnocidios.

El desarraigo de los tasmanianos es interpretado por Darwin como una "gran ventaja" que disfrutan los colonos.

Una masacre es vista en términos positivos, ya que lo que cuenta no es el otro, sino ver el mundo en términos de eficacia: sin nativos, la isla de Tasmania ya se parece bastante más a Irlanda.

La masacre de un pueblo por otro no es, entonces, algo que deba ponderarse en términos de "culpa" o "excesos" sino que no es otra cosa que "un proceso natural".

Bípede, O Diário do Beagle está traduzido por Caetano Waldriges Galindo da UFPR.

Dawin pasó por Río e ficou encantado.

E existe esta outra, te copio la data:

Viagem de um naturalista ao redor do mundo – que a Coleção L&PM Pocket publica em dois volumes – traz os diários mantidos durante essa jornada pelo cientista, que passou pela África, pelas infindáveis costas da América do Sul (inclusive do Brasil), Terra do Fogo, Andes, ilhas Galápagos e Austrália.Tradução de Pedro Gonzaga

Coleção L&PM Pocket

Sí, Gerana, esto fica além da razão.

Publicar un comentario