Dios

Días de tedio inerte y de derrota

y de la frente hundida y pies en fango

en que agobiada la conciencia apenas

puede sufrir a Dios más bien que amarlo.

Ay esperanza, que te fuiste lejos

y el hilo en que me tienes es delgado

suspendido -¿hasta cuándo?- tenazmente

sobre el abierto vórtice... ¿Hasta cuándo?

Saber lo que es morir y lo que sienten

el leproso, la coima y el forzado. ..

Quizá Dios quiera que mañana sirva

mi experiencia del potro y del ergástulo.

Pero entretanto sobre mí el inmenso

decaimiento del que pugna en vano

desolación de ser muy débil para

o matar el deseo o realizarlo.

Mas Dios es grande y mis caminos locos

quien los permite puede enderezarlos

y yo no sé por dónde; pero un día

en Él darán por un portillo arcano.

Mas Dios es Dios, y a mí me falta todo

porque me falta el solo necesario

y no me falta nada más que el único,

y lo imposible, inútil, sobrehumano.

Y la fe oscura dice: "Pero ¿cómo?"

y la esperanza Ansiosa: "Pero

¿cuándo?"

Jauja

*

Yo salí de mis puertos tres esquifes a vela

Y a remo a la procura de la Isla Afortunada

Que son trescientas islas, mas la flor de canela

De todas es la incógnita que denominan Jauja

Hirsuta, impervia al paso de toda carabela

La cedió el Rey de Rodas a su primo el de León

Solo se aborda al precio de naufragio y procela

Y no la hallaron Vasco de Gama ni Colón.

*

Rompí todas mis cosas implacable exterminio

Mi jardín con sus ramos de cedrón y de arauja

Mis libros de Estrabonio de Plutarco y de Plinio

Y dije que iba a América, no dije que iba a Jauja.

Pinté verdes los cascos y los remos de minio

Y las vela como alas de halcón y de ilusión

Quedé sin rey ni patria, refugio ni dominio

Mi madre y su pañuelo llorando en el balcón.

*

Muchas veces la he visto, diferentes facciones,

Diferentes lugares, siempre la misma Jauja

Sus árboles, sus frondas floridas, sus peñones

Sus casas, maderamen del más perito atauja.

Su señuelo hechicero de aromas y canciones

Enfervecía el cielo de mi tripulación,

Mas desaparecían sus mágicas visiones

Apenas la ardua proa tocaba el malecón.

*

La he visto entre las brumas, la he visto en lontananza

A la luz de la luna y al sol de mediodía

Con sus ropas de novia de ensueño y esperanza

Y su cuerpo de engaño decepción y folia.

Esfuerzo de mil años de huracán y bonanza

Empresa irrevocable pues no hay volver atrás

La isla prometida que hechiza y que descansa

Cederá a mis conatos cuando no pueda más.

*

Surqué rabiosas aguas de mares ignorados

Cabalgué sobre olas de violencia inaudita

Sobre mil brazas de agua con cascos escorados

Recorrí la traidora pampa que el sol limita.

Desde el cabo de Hatteras al golfo de Mogados

Dejando atrás la isla que habitó Robinson

Con buena cara al tiempo malo y trucos osados

Al hambre y los motines de la tripulación.

*

Me decían los hombres serios de mi aldehuela

“Si eso fuera seguro con su prueba segura

También me arriesgaría, yo me hiciera a la vela

Pero arriesgarlo todo sin saber es locura...”

Pero arriesgarlo todo justamente es el modo

Pues Jauja significa la decisión total

Y es el riesgo absoluto, y el arriesgarlo todo,

Es la fórmula única para hacerla real.

*

Si estuviera en el mapa y estuviera a la vista

Con correos y viajes de idea y vuelta y recreo

Eso sería negocio, ya no fuera conquista

Y no sería Jauja sino Montevideo.

Dar dos recibir cuatro, cosa es de petardista,

Jauja no es una playa-Hawaii o Miramar.

No la hizo un matemático sino el Gran Novelista

Ni es hecha sino para marineros de mar.

*

Las gentes de los puertos donde iba a bastimento

Risueñas me miraban pasar como a un tilingo

Yo entendía en sus ojos su irónico contento

Aunque nada dijeran o aunque hablaran en gringo.

Doncellas que querían sacarme a salvamento

Me hacían ojos dulces o charlas de pasión

La sangre se me alzaba de sed o sentimiento

Mas yo era como un Sísifo volcando su peñón.

*

Busco la isla de Jauja, sé lo que busco y quiero

Que buscaron los grandes y han encontrado pocos

El naufragio es seguro y es la ley del crucero

Pues los que quieren verla sin naufragar, son locos

Quieren llegar a ella sano y limpio el esquife

Seca la ropa y todos los bagajes en paz

Cuando sólo se arriba lanzando al arrecife

El bote y atacando desnudo a nado el caz.

*

Busco la isla de Jauja de mis puertos orzando

Y echando a un solo dado mi vida y mi fortuna;

La he visto muchas veces de mi puente de mando

Al sol de mediodía o a la luz de la luna.

Mis galeotes de balde me lloran ¿cuándo, cuándo?

Ni les perdono el remo, ni les cedo el timón.

Este es el viaje eterno que es siempre comenzando

Pero el término incierto canta en mi corazón.

*

Oración

*

Gracias te doy Dios mío que me diste un hermano

Que aunque sea invisible me acompaña y espera

Claro que no lo he visto, pretenderlo era vano

Pues murió varios siglos antes que yo naciera

Mas me dejó su libro que, diccionario en mano,

De la lengua danesa voy traduciendo yo

Y se ve por la pinta del fraseo baquiano

que él llegó, que él llegó.

*

Yo salí de mis puertos tres esquifes a vela

Y a remo a la procura de la Isla Afortunada

Que son trescientas islas, mas la flor de canela

De todas es la incógnita que denominan Jauja

Hirsuta, impervia al paso de toda carabela

La cedió el Rey de Rodas a su primo el de León

Solo se aborda al precio de naufragio y procela

Y no la hallaron Vasco de Gama ni Colón.

*

Rompí todas mis cosas implacable exterminio

Mi jardín con sus ramos de cedrón y de arauja

Mis libros de Estrabonio de Plutarco y de Plinio

Y dije que iba a América, no dije que iba a Jauja.

Pinté verdes los cascos y los remos de minio

Y las vela como alas de halcón y de ilusión

Quedé sin rey ni patria, refugio ni dominio

Mi madre y su pañuelo llorando en el balcón.

*

Muchas veces la he visto, diferentes facciones,

Diferentes lugares, siempre la misma Jauja

Sus árboles, sus frondas floridas, sus peñones

Sus casas, maderamen del más perito atauja.

Su señuelo hechicero de aromas y canciones

Enfervecía el cielo de mi tripulación,

Mas desaparecían sus mágicas visiones

Apenas la ardua proa tocaba el malecón.

*

La he visto entre las brumas, la he visto en lontananza

A la luz de la luna y al sol de mediodía

Con sus ropas de novia de ensueño y esperanza

Y su cuerpo de engaño decepción y folia.

Esfuerzo de mil años de huracán y bonanza

Empresa irrevocable pues no hay volver atrás

La isla prometida que hechiza y que descansa

Cederá a mis conatos cuando no pueda más.

*

Surqué rabiosas aguas de mares ignorados

Cabalgué sobre olas de violencia inaudita

Sobre mil brazas de agua con cascos escorados

Recorrí la traidora pampa que el sol limita.

Desde el cabo de Hatteras al golfo de Mogados

Dejando atrás la isla que habitó Robinson

Con buena cara al tiempo malo y trucos osados

Al hambre y los motines de la tripulación.

*

Me decían los hombres serios de mi aldehuela

“Si eso fuera seguro con su prueba segura

También me arriesgaría, yo me hiciera a la vela

Pero arriesgarlo todo sin saber es locura...”

Pero arriesgarlo todo justamente es el modo

Pues Jauja significa la decisión total

Y es el riesgo absoluto, y el arriesgarlo todo,

Es la fórmula única para hacerla real.

*

Si estuviera en el mapa y estuviera a la vista

Con correos y viajes de idea y vuelta y recreo

Eso sería negocio, ya no fuera conquista

Y no sería Jauja sino Montevideo.

Dar dos recibir cuatro, cosa es de petardista,

Jauja no es una playa-Hawaii o Miramar.

No la hizo un matemático sino el Gran Novelista

Ni es hecha sino para marineros de mar.

*

Las gentes de los puertos donde iba a bastimento

Risueñas me miraban pasar como a un tilingo

Yo entendía en sus ojos su irónico contento

Aunque nada dijeran o aunque hablaran en gringo.

Doncellas que querían sacarme a salvamento

Me hacían ojos dulces o charlas de pasión

La sangre se me alzaba de sed o sentimiento

Mas yo era como un Sísifo volcando su peñón.

*

Busco la isla de Jauja, sé lo que busco y quiero

Que buscaron los grandes y han encontrado pocos

El naufragio es seguro y es la ley del crucero

Pues los que quieren verla sin naufragar, son locos

Quieren llegar a ella sano y limpio el esquife

Seca la ropa y todos los bagajes en paz

Cuando sólo se arriba lanzando al arrecife

El bote y atacando desnudo a nado el caz.

*

Busco la isla de Jauja de mis puertos orzando

Y echando a un solo dado mi vida y mi fortuna;

La he visto muchas veces de mi puente de mando

Al sol de mediodía o a la luz de la luna.

Mis galeotes de balde me lloran ¿cuándo, cuándo?

Ni les perdono el remo, ni les cedo el timón.

Este es el viaje eterno que es siempre comenzando

Pero el término incierto canta en mi corazón.

*

Oración

*

Gracias te doy Dios mío que me diste un hermano

Que aunque sea invisible me acompaña y espera

Claro que no lo he visto, pretenderlo era vano

Pues murió varios siglos antes que yo naciera

Mas me dejó su libro que, diccionario en mano,

De la lengua danesa voy traduciendo yo

Y se ve por la pinta del fraseo baquiano

que él llegó, que él llegó.

*

(Poema con que finaliza el ensayo De Kirkegord a Tomás de Aquino de Leonardo Castellani)

Oración de Santo Tomás por la

sabiduría

Omnia haec, oh

Reginalde, mihi jam videntur quasi palea.

Luz de la luz y rosa de la rosa

foco y fuente de todo lo que es vida

que pretendo apresar con mi atrevida

torre de silogismos rigurosa,

Tripersonal natura misteriosa

inaccesible intelectual guarida

de quien el hombre sueña y el suicida

muere, y el cosmos vive, el ángel goza ...

En piedra de razón, luz de sagrario

y cemento de humano pensamiento

de mi summa el andamio extraordinario

he levantado en inaudito intento...

Quiero que un soplo tuyo lo haga viento

lo haga música mística tu aliento

y un rayo lo haga polvo de incensario.

DIOS NO ES UN CANTOR DE TANGO

Opinar y a fondo, fue siempre un saludable hábito del padre Castellani. A los 80 años, mientras, como el dice, se prepara para morir, afronta todas las preguntas. No titubea en asumir los temas trascendentes y los más inmediatos, los referidos a la Argentina de hoy.

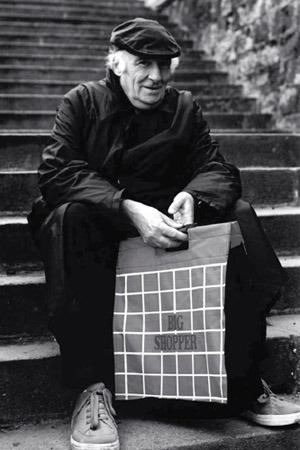

DE PROFESIÓN PENSADOR. A pocos se les puede decir eso. Al padre Castellani sí. En la foto, con SIETE DÍAS. “No es verdad que al pueblo haya que defenderlo aun contra su voluntad, como a los chicos. A los pueblos hay que enseñarles, en todo caso, a no ser chicos…”

No hay nada que hacerle: somos pedantes o ilusos. Cuando escribimos un reportaje en entregas, al final damos por hecho que el lector ya leyó lo anterior. Pero casi nunca es así. Por eso sacrificamos nuestra pedantería o nuestra ilusa ilusión y hacemos de cuenta lo más probable, que el lector pasó por alto lo anterior. Desandamos rápidamente lo andado.

El padre Leonardo Castellani tiene 80 años, casi 60 libros y una erudición, humor y espíritu crítico que muy pocos argentinos de este siglo han tenido. Peleó con todos, menos con Dios.

Padeció cesantías. Vivió desterrado, enfermo y al borde de la locura, por sus conflictos dentro de la Iglesia.

El padre Leonardo Castellani tiene 80 años, casi 60 libros y una erudición, humor y espíritu crítico que muy pocos argentinos de este siglo han tenido. Peleó con todos, menos con Dios.

Padeció cesantías. Vivió desterrado, enfermo y al borde de la locura, por sus conflictos dentro de la Iglesia.

Juan XXIII le devolvió sus facultades sacerdotales y la celebración de la misa. Escribió cuentos policiales, teología, poesía, teatro, ensayos, periodismo. Aunque en veredas muy opuestas, lo comparamos por su volumen al mismísimo Borges, y por esa forma frontal de asumir todos los asuntos a su muy aborrecido Jean Paul Sartre. En la actualidad este pensador vive arrinconado. Es un enorme desconocido. Otro lujo que nos damos los argentinos, en medio del desierto y la chatura.

A la primera charla de esta serie el padre Castellani la cerró con una dulce frase, que nos viene muy al caso: "La aguja pasa y queda el hilo. Lo político pasa y queda lo moral. Pero si la aguja no tiene hilo, la aguja pasa y no queda nada."

De la segunda charla memorizamos otras dos frases. La primera: "Dado que el periodista tiene que decir algo, ¿por qué no dice la verdad de vez en cuando?" La segunda: "Si esto sigue así lo mejor que podemos hacer es entrar en la Sociedad Protectora de Animales no como protectores sino como protegidos." Después de esa "sugerencia" el padre Castellani hizo lo que varias veces durante nuestra entrevista: volcó la cabeza y se dispuso a dormir un rato.

El rato otra vez pasó. Y la charla prosigue con la palabra que viene de la voz o a veces de la palabra ya escrita del padre Castellani, que comete un delito que muy pocos pueden cometer: “se afana a sí mismo”.

-Usted, padre, ha hecho teología y periodismo, ¿cómo es posible?

-Yo creo, como Kirkegord, que el periodismo de hoy es una gran porquería, pero una porquería necesaria, buena. Yo depuse mi pedantería y prediqué el Evangelio mediante él. Pero sé que a medida que aumentan las noticias disminuyen las verdades y así se promueve una especie cada vez más difundida, la del lector analfabeto. No puedo negarlo, soy periodista y lo reconozco como una actividad tan frívola como febril y un poco sucia, aunque nada impide que un hombre honrado, ayudando a Dios, pueda ejercerla, eso sí, vestido de limpiachimeneas, o cloaquero de tercera clase.

-Como periodista o predicador del Evangelio, ¿usted qué cosas ha repiqueteado, qué conclusiones tiene a esta altura del siglo o del baile?

-Demasiada pregunta para mi cansancio, pero le respondo con lo que alguna vez escribí... somos una nación degradada, subvertida en sus valores, sin fundamento, sin asiento, sin seriedad... por causa de una educación que ni siquiera ha sido mala educación, nos hemos convertido en una sementera de tilingos, en el paraíso de los ladrones y, en ciertos momentos grotescos, en la polichinela del mundo. Muchas veces me pregunto si, para ser eso que progresivamente somos no hubiese sido mejor ser una colonia como Canadá. Digo esto por algo bien concreto y que sería maula callar los pueblos distorsionados y corrompidos no pueden ser independientes, ni les conviene tampoco.

-¿Usted no cree, padre, ni siquiera en eso que se llama “patriotismo”?

-Creo demasiado en el patriotismo, ¡pero cuidado con la endemoniada palabra! Es buen momento para recordar que no todo patriotismo es una virtud. Muchas veces puede ser un vicio o una alharaca. Hay preguntas para hacer: “sí no amas al prójimo, al que ves, ¿cómo amarás a la patria, a la que no ves?” Por otra parte tenemos que reconocer que a veces a la patria no se la puede amar, sólo se la puede compadecer. Creo que es legítimo preguntarse: cuando Jesucristo lloraba sobre Jerusalén, ¿lloraba porque la amaba? Yo digo que no: no podía amar a esa gran porquería en que se había convertido un estado que estaba bajo la dirección del hipócrita Caifás, el payaso Herodes y el poder efectivo de una potencia extranjera.

Se produce una pausa. El padre Castellani toma un té con una vainilla. Duerme unos diez minutos. Despierta.

-Padre Castellani, usted tiene "fama" de muchas cosas. Por ejemplo, fama de admirar a los dictadores. ¿Qué dice de eso?

-Tengo fama de cosas peores, pero no me aflige, Dios me está esperando. Le digo qué sí, pero con una leve advertencia para maulas de café... los nacionalistas y no nacionalistas muchas veces han querido imponer dictatorialmente la moral a toda esta nación, pero han fracasado. Porque no eran dictadores de verdad...

-¿Cómo debe ser un “dictador de verdad”?

-Es necesario que sea santo. “Porque el grado de violencia que un hombre tiene derecho de infligir a otros hombres corresponde, por lo menos, al grado de amor que les tiene. La violencia infligida por el odio es siempre contagiosa y volvedora: rebota sobre el violento.”-Otras de sus famas, padre Castellani, es que usted, cosa rara en un intelectual, aprueba la pena de muerte.

-Sobre esto escribí, y me repito: bien mirada la pena de muerte es más “cristiana” que la prisión perpetua, que no hace sino pudrir al criminal y no lo convierte ni mejora. Jesucristo no reprobó la pena de muerte. Al fin y al cabo para un cristiano es preferible la salvación del alma del injusto que la conservación de su vida para que la pierda. Ahora bien, aquí ahora en la Argentina la pena de muerte me parece discutible y peligrosa. Puede servir para cualquier cosa. Para aplicarla hace falta poseer el sentido de lo sagrado, cosa disminuida y pereciente entre nosotros.

Pausa. Pero no para dormir, sino para caminar. Vamos hasta parque Lezama. Y allí caminamos unos metros con el padre Castellani. Caminamos muy lentamente. A pasitos. Después de los 40 metros, me dice casi implorando: “Las pantorrillas, me duelen las pantorrillas. ¿Nos podremos sentar?” Eso hacemos. La gente pasa. Nadie sabe quién es este anciano sacerdote, de gran capa. Evidentemente, el padre Castellani no tiene “rating”. Nadie lo conoce. Será porque, como dijimos, carga el estigma de no haber almorzado nunca por televisión. Y eso es más o menos como no haber nacido.

Pero este hombre, que, ahora tose y tose y acude al aire para doblegar a su creciente fatiga, este hombre nació, y vive, y vivirá porque ha escrito, y en castellano. Ha escrito por ejemplo: “Al pueblo hay que defenderlo aun contra su voluntad - dijo uno-, como a los chicos. No es verdad, a los pueblos hay que enseñarles, en todo caso, a no ser chicos.”

Este hombre, que ahora ya ha sosegado su tos, cuenta que una vez su confesor le dijo:“Castellani, usted no piense más en el petróleo. Usted es religioso y debe pensar en Dios. Dios no come petróleo.” Y él le contestó: "Dios no come petróleo, pero el diablo sí."

En el banco del parque el diálogo continúa, mientras afuera la vida y el país prosiguen, y los pajaritos cantan:

Lo que puede ver de nuestro presente, ¿qué le parece, padre Castellani?

-Yo no creo que todo tiempo pasado fue mejor, a mí me sigue pareciendo igual... igual de malo.

-¿De dónde proviene esto que califica así?

-De la escuela. No es lo peor de nuestra escuela que sea irreligiosa; lo peor es que sea ineficaz, no es escuela. Los argentinos no salimos del bachillerato maduros. La mayoría sale mentalmente averiado, predestinados para ser tilingos incurables. Así es que desembocamos en esta queja nacional, la de no tener clase dirigente. No la hay en ningún sector, no sólo en el sector político. Es una lamentable y llorable realidad. O irrealidad: es un vacío. Y como la naturaleza no. soporta el vacío, este vacío es llenado por una seudo clase dirigente. En cuanto a lo político, hay pocas vocaciones y las que hay se malogran. No hay cómo entrenarse de estadista. Los estadistas no nacen de los repollos.

-Y más allá o más acá de la clase dirigente, ¿qué ve? -No veo al héroe que sea capaz de dar el golpe de timón, no veo los grupos unidos capaces de secundar al héroe; no veo ni siquiera la masa consciente por lo menos del mal... veo una comunidad satisfecha de su degeneración cuyo ideal sería una esclavitud confortable.

-Usted a Dios lo nombra como alguien corporal, ¿en este minuto puede decir algo sobre El?

-Que Dios está faltando, nos está faltando. Además, lo confundimos, Dios es un hidalgo, no es un cantor de tango.

Descamina muy lentamente lo caminado. Al llegar a su ámbito el padre CasteIlani sufre una descompostura, se recupera. Seguimos:

-¿Usted está lejos o cerca de la santidad?

-He conocido pocos santos, ninguno. En cuanto a mi, lejos estoy de serlo. Por lo demás, a mi no me van a canonizar, aunque lo quiera Jesucristo; en serio, porque la maquinaria canonizadora puede resistir a Jesucristo. A mi me han aporreado mucho, será por aquello de "porque te quiero, te aporreo. Mejor que no me quisieran tanto. Ahora aguardo, aguardo y procuro vivir con serenidad nuestra desesperanza, aunque siempre hay algo que se puede hacer. En fin, estoy viviendo una de las peores culpas que hay, que es la de ser viejo. Contra los años nadie es valiente.

-Usted está por comer, le hago la pregunta más tonta, la de siempre: ¿Quiere agregar algo más?

-Lo mismo que escribí cuando cerré la revista "Jauja". Si hay perdón para decir la verdad, aunque decirla sea peligroso, que Dios me perdone; pero ya con una pata en el sepulcro, ¿qué puedo hacer de provecho sino decir la verdad? Eso es para mí hacer penitencia. Así preparo una buena muerte.

El padre Castellani, en una mesita en la que sólo cabe un plato, empieza a comer. Ahí está el pensador. Ahí está el hombre que, por haber sido agraciado con el Gran Premio de Consagración Nacional, recibe una pensión mensual de ocho millones y medio de pesos viejos, muy viejos.

No, "en fin" no. Nos queda, muy pendiente, una pregunta inevitable: ¿Qué le pasa a un país que ignora y arrincona tan alevosamente a sus hombres que piensan?

A la primera charla de esta serie el padre Castellani la cerró con una dulce frase, que nos viene muy al caso: "La aguja pasa y queda el hilo. Lo político pasa y queda lo moral. Pero si la aguja no tiene hilo, la aguja pasa y no queda nada."

De la segunda charla memorizamos otras dos frases. La primera: "Dado que el periodista tiene que decir algo, ¿por qué no dice la verdad de vez en cuando?" La segunda: "Si esto sigue así lo mejor que podemos hacer es entrar en la Sociedad Protectora de Animales no como protectores sino como protegidos." Después de esa "sugerencia" el padre Castellani hizo lo que varias veces durante nuestra entrevista: volcó la cabeza y se dispuso a dormir un rato.

El rato otra vez pasó. Y la charla prosigue con la palabra que viene de la voz o a veces de la palabra ya escrita del padre Castellani, que comete un delito que muy pocos pueden cometer: “se afana a sí mismo”.

-Usted, padre, ha hecho teología y periodismo, ¿cómo es posible?

-Yo creo, como Kirkegord, que el periodismo de hoy es una gran porquería, pero una porquería necesaria, buena. Yo depuse mi pedantería y prediqué el Evangelio mediante él. Pero sé que a medida que aumentan las noticias disminuyen las verdades y así se promueve una especie cada vez más difundida, la del lector analfabeto. No puedo negarlo, soy periodista y lo reconozco como una actividad tan frívola como febril y un poco sucia, aunque nada impide que un hombre honrado, ayudando a Dios, pueda ejercerla, eso sí, vestido de limpiachimeneas, o cloaquero de tercera clase.

-Como periodista o predicador del Evangelio, ¿usted qué cosas ha repiqueteado, qué conclusiones tiene a esta altura del siglo o del baile?

-Demasiada pregunta para mi cansancio, pero le respondo con lo que alguna vez escribí... somos una nación degradada, subvertida en sus valores, sin fundamento, sin asiento, sin seriedad... por causa de una educación que ni siquiera ha sido mala educación, nos hemos convertido en una sementera de tilingos, en el paraíso de los ladrones y, en ciertos momentos grotescos, en la polichinela del mundo. Muchas veces me pregunto si, para ser eso que progresivamente somos no hubiese sido mejor ser una colonia como Canadá. Digo esto por algo bien concreto y que sería maula callar los pueblos distorsionados y corrompidos no pueden ser independientes, ni les conviene tampoco.

-¿Usted no cree, padre, ni siquiera en eso que se llama “patriotismo”?

-Creo demasiado en el patriotismo, ¡pero cuidado con la endemoniada palabra! Es buen momento para recordar que no todo patriotismo es una virtud. Muchas veces puede ser un vicio o una alharaca. Hay preguntas para hacer: “sí no amas al prójimo, al que ves, ¿cómo amarás a la patria, a la que no ves?” Por otra parte tenemos que reconocer que a veces a la patria no se la puede amar, sólo se la puede compadecer. Creo que es legítimo preguntarse: cuando Jesucristo lloraba sobre Jerusalén, ¿lloraba porque la amaba? Yo digo que no: no podía amar a esa gran porquería en que se había convertido un estado que estaba bajo la dirección del hipócrita Caifás, el payaso Herodes y el poder efectivo de una potencia extranjera.

Se produce una pausa. El padre Castellani toma un té con una vainilla. Duerme unos diez minutos. Despierta.

-Padre Castellani, usted tiene "fama" de muchas cosas. Por ejemplo, fama de admirar a los dictadores. ¿Qué dice de eso?

-Tengo fama de cosas peores, pero no me aflige, Dios me está esperando. Le digo qué sí, pero con una leve advertencia para maulas de café... los nacionalistas y no nacionalistas muchas veces han querido imponer dictatorialmente la moral a toda esta nación, pero han fracasado. Porque no eran dictadores de verdad...

-¿Cómo debe ser un “dictador de verdad”?

-Es necesario que sea santo. “Porque el grado de violencia que un hombre tiene derecho de infligir a otros hombres corresponde, por lo menos, al grado de amor que les tiene. La violencia infligida por el odio es siempre contagiosa y volvedora: rebota sobre el violento.”-Otras de sus famas, padre Castellani, es que usted, cosa rara en un intelectual, aprueba la pena de muerte.

-Sobre esto escribí, y me repito: bien mirada la pena de muerte es más “cristiana” que la prisión perpetua, que no hace sino pudrir al criminal y no lo convierte ni mejora. Jesucristo no reprobó la pena de muerte. Al fin y al cabo para un cristiano es preferible la salvación del alma del injusto que la conservación de su vida para que la pierda. Ahora bien, aquí ahora en la Argentina la pena de muerte me parece discutible y peligrosa. Puede servir para cualquier cosa. Para aplicarla hace falta poseer el sentido de lo sagrado, cosa disminuida y pereciente entre nosotros.

Pausa. Pero no para dormir, sino para caminar. Vamos hasta parque Lezama. Y allí caminamos unos metros con el padre Castellani. Caminamos muy lentamente. A pasitos. Después de los 40 metros, me dice casi implorando: “Las pantorrillas, me duelen las pantorrillas. ¿Nos podremos sentar?” Eso hacemos. La gente pasa. Nadie sabe quién es este anciano sacerdote, de gran capa. Evidentemente, el padre Castellani no tiene “rating”. Nadie lo conoce. Será porque, como dijimos, carga el estigma de no haber almorzado nunca por televisión. Y eso es más o menos como no haber nacido.

Pero este hombre, que, ahora tose y tose y acude al aire para doblegar a su creciente fatiga, este hombre nació, y vive, y vivirá porque ha escrito, y en castellano. Ha escrito por ejemplo: “Al pueblo hay que defenderlo aun contra su voluntad - dijo uno-, como a los chicos. No es verdad, a los pueblos hay que enseñarles, en todo caso, a no ser chicos.”

Este hombre, que ahora ya ha sosegado su tos, cuenta que una vez su confesor le dijo:“Castellani, usted no piense más en el petróleo. Usted es religioso y debe pensar en Dios. Dios no come petróleo.” Y él le contestó: "Dios no come petróleo, pero el diablo sí."

En el banco del parque el diálogo continúa, mientras afuera la vida y el país prosiguen, y los pajaritos cantan:

Lo que puede ver de nuestro presente, ¿qué le parece, padre Castellani?

-Yo no creo que todo tiempo pasado fue mejor, a mí me sigue pareciendo igual... igual de malo.

-¿De dónde proviene esto que califica así?

-De la escuela. No es lo peor de nuestra escuela que sea irreligiosa; lo peor es que sea ineficaz, no es escuela. Los argentinos no salimos del bachillerato maduros. La mayoría sale mentalmente averiado, predestinados para ser tilingos incurables. Así es que desembocamos en esta queja nacional, la de no tener clase dirigente. No la hay en ningún sector, no sólo en el sector político. Es una lamentable y llorable realidad. O irrealidad: es un vacío. Y como la naturaleza no. soporta el vacío, este vacío es llenado por una seudo clase dirigente. En cuanto a lo político, hay pocas vocaciones y las que hay se malogran. No hay cómo entrenarse de estadista. Los estadistas no nacen de los repollos.

-Y más allá o más acá de la clase dirigente, ¿qué ve? -No veo al héroe que sea capaz de dar el golpe de timón, no veo los grupos unidos capaces de secundar al héroe; no veo ni siquiera la masa consciente por lo menos del mal... veo una comunidad satisfecha de su degeneración cuyo ideal sería una esclavitud confortable.

-Usted a Dios lo nombra como alguien corporal, ¿en este minuto puede decir algo sobre El?

-Que Dios está faltando, nos está faltando. Además, lo confundimos, Dios es un hidalgo, no es un cantor de tango.

Descamina muy lentamente lo caminado. Al llegar a su ámbito el padre CasteIlani sufre una descompostura, se recupera. Seguimos:

-¿Usted está lejos o cerca de la santidad?

-He conocido pocos santos, ninguno. En cuanto a mi, lejos estoy de serlo. Por lo demás, a mi no me van a canonizar, aunque lo quiera Jesucristo; en serio, porque la maquinaria canonizadora puede resistir a Jesucristo. A mi me han aporreado mucho, será por aquello de "porque te quiero, te aporreo. Mejor que no me quisieran tanto. Ahora aguardo, aguardo y procuro vivir con serenidad nuestra desesperanza, aunque siempre hay algo que se puede hacer. En fin, estoy viviendo una de las peores culpas que hay, que es la de ser viejo. Contra los años nadie es valiente.

-Usted está por comer, le hago la pregunta más tonta, la de siempre: ¿Quiere agregar algo más?

-Lo mismo que escribí cuando cerré la revista "Jauja". Si hay perdón para decir la verdad, aunque decirla sea peligroso, que Dios me perdone; pero ya con una pata en el sepulcro, ¿qué puedo hacer de provecho sino decir la verdad? Eso es para mí hacer penitencia. Así preparo una buena muerte.

El padre Castellani, en una mesita en la que sólo cabe un plato, empieza a comer. Ahí está el pensador. Ahí está el hombre que, por haber sido agraciado con el Gran Premio de Consagración Nacional, recibe una pensión mensual de ocho millones y medio de pesos viejos, muy viejos.

No, "en fin" no. Nos queda, muy pendiente, una pregunta inevitable: ¿Qué le pasa a un país que ignora y arrincona tan alevosamente a sus hombres que piensan?

“Ya con una pata en el sepulcro ¿qué puedo hacer de provecho si no decir la verdad? Así hago penitencia”

AÑO 1955. DE CIVIL. La foto, extraña, corresponde a un documento de identidad.

Había sido cesanteado como profesor. Optó por el periodismo para comentar el Evangelio.

LA "MESA" DEL PENSADOR. El padre Castellani atendido por la profesora Caminos. Así almuerza. Come poquito. Esto es una suerte, ante sus magros ingresos.

Rodolfo E. Braceli.

Misterios y maledicencias en torno al padre Castellani

Horacio Vázquez-Rial

La fortuna quiso que yo llegara a conocer al padre Leonardo Castellani poco antes de mi apresurada salida de la Argentina, con la que salvé mi vida. También conocí, y traté bastante en Barcelona, a Eduardo Galeano, Eduardo Hughes Galeano, quien ha abdicado del apellido paterno, que lo hace gringo y pariente lejano de Perón.

Hasta hace poco, todo el mundo sabía quién era Galeano porque Las venas abiertas de América Latina no era sólo el regalo de Hugo Chávez a Obama, sino el libro más leído que se haya escrito sobre el tema, y uno de los más duraderos best sellers de la historia.

Pocos libros tan falaces y seductores como el de Galeano. Él también es un tipo seductor. Tal vez por eso, y por su brillante papel como editor del semanario Marcha de Montevideo, le confió Federico Vogelius los dineros necesarios para publicar la revista Crisis, que marcó una época del periodismo rioplatense generando ideología para la izquierda más confusa del mundo. En esa revista, referente de aquel tiempo, apareció una entrevista al padre Castellani en julio de 1976, poco antes de que la cerrara la dictadura, que se había iniciado formalmente el 24 de marzo anterior. (La dictadura ya era tal desde los tiempos inmediatos a la muerte del general Perón, y la viuda de éste ya había encargado a Videla que aniquilara la guerrilla).

El golpe de estado tuvo lugar el 24 de marzo de 1976. El 19 de mayo Videla invitó a comer a la Casa de Gobierno a cuatro escritores: Jorge Luis Borges, Ernesto Sábato, Leonardo Castellani y, por ser el presidente de la SADE (Sociedad Argentina de Escritores), Horacio Esteban Ratti, que en modo alguno estaba a la altura de los demás pero se suponía que representaba al gremio. Por La Opinión del día siguiente y La Razón, vespertino del mismo día 19, se conoció la visión de los participantes. Sábato, que años después presidiría la Conadep (Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas), evidenciando su incombustibilidad, declaró al diario de Jacobo Timerman que hubo "un altísimo grado de comprensión y respeto mutuos" y que "en ningún momento la conversación descendió [sic] a la polémica literaria o ideológica". En La Razón dejó constancia de haber expresado su inquietud por la detención del escritor Antonio Di Benedetto. Borges no declaró nada. Lo había hecho antes, con una vuelta muy suya para no quedarse pegado a nada: "Soy tímido y, ante tanta gente importante, seguramente me sentiré abochornado". Ratti habló de lo suyo: derechos de autor, ley del libro, designación de asesores literarios en emisoras de radio y TV y agregados diplomáticos culturales en el exterior: no perder puestos de trabajo.

Todo esto lo leo ahora en el aludido número de Crisis de julio de 1976, que quiso entrevistar a los cuatro. Borges se escabulló. Sábato dijo que no daba entrevistas a Crisis: todavía no era su momento de ocuparse de los desaparecidos que ya estaban desapareciendo. O sea que hablaron Ratti y Castellani. El primero mencionó el hecho de que entregó a Videla ("Nos impresionó a todos como un hombre muy comprensivo e inteligente") una lista con 16 nombres. Esos nombres eran los de Haroldo Conti, Alberto Costa y Carlos Pérez, desparecidos; Antonio Di Benedetto, preso, y César Tiempo (a quien habían echado de la dirección de Teatro Nacional Cervantes, lo que equivalía a un anuncio de desgracia inminente, cosa que en este caso no se cumplió); a los que en los días siguientes se añadirían los del cineasta Raimundo Gleizer y el periodista Miguel Ángel Bustos.

Todo esto lo leo ahora en el aludido número de Crisis de julio de 1976, que quiso entrevistar a los cuatro. Borges se escabulló. Sábato dijo que no daba entrevistas a Crisis: todavía no era su momento de ocuparse de los desaparecidos que ya estaban desapareciendo. O sea que hablaron Ratti y Castellani. El primero mencionó el hecho de que entregó a Videla ("Nos impresionó a todos como un hombre muy comprensivo e inteligente") una lista con 16 nombres. Esos nombres eran los de Haroldo Conti, Alberto Costa y Carlos Pérez, desparecidos; Antonio Di Benedetto, preso, y César Tiempo (a quien habían echado de la dirección de Teatro Nacional Cervantes, lo que equivalía a un anuncio de desgracia inminente, cosa que en este caso no se cumplió); a los que en los días siguientes se añadirían los del cineasta Raimundo Gleizer y el periodista Miguel Ángel Bustos.

Lo interesante aquí, sin embargo, no es nada de eso, archisabido y listado, sino la mal recordada participación de Leonardo Castellani, que sí hablo conCrisis, y sin pelos en la lengua. Después de señalar que "fue nada más que un almuerzo y en los almuerzos se come más que se habla", y que "el más callado" fue él, afirmó: "Los que más hablaron fueron Sábato y Ratti, que llevaban varios proyectos". Reproduzco a continuación fragmentos de la entrevista, que ya es documento histórico:

–¿Y el presidente?

–Él y yo fuimos los más silenciosos. Videla se limitó a escuchar. Creo que lo que sucedió fue que los que más hablaron, en vez de preguntar, hicieron demasiadas propuestas. En mi criterio, ninguna de ellas fue importante, porque estaban centradas en lo cultural y soslayaban lo político. Sábato y Ratti hablaron mucho sobre la ley del libro, sobre el problema de la SADE, sobre los derechos de autor, etc.

–Bueno, padre, al fin y al cabo, era una reunión de escritores...

–Sí, pero la preocupación central de un escritor nunca pueden ser los libros, ¿no es cierto? Yo traté de aprovechar la situación por lo menos con una inquietud que llevaba en mi corazón de cristiano. Días atrás me había visitado una persona que, con lágrimas en los ojos, sumida en la desesperación, me había suplicado que intercediera por la vida del escritor Haroldo Conti. Yo no sabía de él más que era un escritor prestigioso y que había sido seminarista en su juventud. Pero, de cualquier manera, no me importaba eso, pues, así se hubiera tratado de cualquier persona, mi obligación moral era hacerme eco de quien pedía por alguien cuyo destino es incierto en estos momentos. Anoté su nombre en un papel y se lo entregué a Videla, quien lo recogió respetuosamente y aseguró que la paz iba a volver muy pronto al país.

–¿Qué afirmaron los demás asistentes?

–Fíjese qué curioso: Borges y Sábato, en un momento de la reunión, dijeron que el país nunca había sido purificado por una guerra internacional. Ellos, más tarde lo negaron, así como aseguraron decir cosas que, en realidad, no dijeron. Pero hablaron de la purificación por la guerra. Lo interesante es que el presidente Videla, que es un general, un profesional de la guerra, los interrumpió para manifestar su desacuerdo. Creo que eso le desagradó mucho, pues motivó una de sus pocas intervenciones. A mí también eso me cayó como un balde de agua fría, por lo tremendo que eso significa. Además, por lo incorrecto: se olvidan que la Argentina atravesó varias guerras internacionales, como la de la independencia, la del bloqueo anglo-francés, la del Paraguay, y más bien que de esas contiendas no salió purificada.

–Quizás ellos quisieron decir que la situación difícil de la Argentina no se justifica, pues, a diferencia de Europa, no había sufrido ninguna guerra...

–Vea, en lo que va de este siglo Europa sufrió ya dos guerras mundiales pero no por eso es más pura que la Argentina. Al contrario... Por eso le digo que de ese almuerzo, si es por lo que se habló, no puede haber salido algo muy positivo o trascendente. A lo mejor, el presidente se llevó una impresión favorable y pudo rescatar algunas cosas que allí se lanzaron, pero nada más.

–Su balance, entonces, no parece muy optimista...

–No, ni puede serlo. Sábato hablo mucho, o peroró, mejor dicho, sobre el nombramiento de un consejo de notables que supervisara los programas de televisión. En Inglaterra funciona una instancia similar, presidida por la familia real e integrada por hombres notorios de todas las tendencias. Cuando estuve hace mucho en Inglaterra, Chesterton me habló de ese consejo, del cual formaba parte, y que, por aquel entonces, supervisaba sólo la radio, ya que la televisión todavía no existía. Eso quería Sábato que se hiciese en la Argentina. Borges dijo que él no integraría jamás ese consejo de prohombres. Sábato, entonces, dijo que él tampoco. Yo pensé en ese momento por qué lo proponían entonces. O sea que ellos embarcaban a la gente pero se quedaban en tierra. Personalmente, no creo que ese consejo sea una decisión muy importante...

–Dentro de su larga experiencia, ¿qué significa ese almuerzo?

–Para mí fue un hecho agradable, pero no muy trascendente. A menos que los hechos posteriores demuestren lo contrario, como por ejemplo que aparezca el escritor Haroldo Conti. Algunos me habían pedido que intercediera también por varios ex funcionarios cesanteados aparentemente en forma injusta. Pero no quise hacerlo, pues me pareció que esos casos desdibujarían la dramaticidad de la situación de Conti, por cuya vida se teme...

–¿No se plantearon los cuatro asistentes hacer un balance juntos de esa experiencia que los involucraba?

–Al salir, había una nube de periodistas y los fotógrafos eran interminables, parecían formar de seis en fondo. Borges aprovechó algún vericueto para retirarse rápidamente. Cuando Sábato, Ratti y yo logramos zafarnos del asedio periodístico, nos fuimos hasta la casa de Borges, pero ahí nos llevamos una sorpresa. Una persona que nos abrió la puerta dijo que Borges no nos podía atender porque estaba en cama con fuertes dolores de estómago. En fin, son cosas que pasan...

Puedo imaginar perfectamente al pomposo Sábato diciendo "pelotudeces pomposas" (la fórmula le pertenece, no me la invento para el caso, lo dijo él sobre otro) hablando de censurar la radio y la tele: no le bastó, pero el rechazo generó en él tanto resentimiento (añadido a sus ya abundantes resentimientos) que seis años después le vendió a Alfonsín (muy amigo también de las pelotudeces pomposas) la conveniencia de instalar a un notable, es decir, él mismo, al frente de la Conadep.

Puedo imaginar perfectamente a Borges huyendo de aquella trampa y de sus pares: el hombre no estaba hecho para esas cosas. Ratti, por su parte, se reiteraría a sí mismo, valedor de sus colegas a falta de algo (literariamente) mejor que hacer.

El tono del relato de Castellani me parece auténtico: era un tipo sencillo, la antítesis de Sábato, de quien Chesterton se hubiese reído mucho. Y, lo más importante en todo esto, el motivo por el cual he querido traer aquí la figura del sacerdote escritor: todo en sus palabras habla de su preocupación auténtica por la vida de Conti, y su sabia visión de la dictadura: era el único que la veía con claridad como tal, que no se dejaba engañar, que condicionaba a demostraciones posteriores de buena voluntad de Videla, como la aparición de desaparecidos, su confianza en el gobierno.

Relatos recibidos mucho después estuvieron dirigidos a ensombrecer la memoria del padre Castellani. Alguien que aseguró haber escuchado de un testigo –trasladado de donde habría estado con Conti a otro campo de detención– que Castellani habría visitado a Conti y, en vez de haber peleado por él, se habría limitado a darle la extremaunción, como le pedía el preso, ya seguro de que los iban a matar. La verdad es que una cosa no excluye la otra. Como sacerdote, le hubiese sido difícil negar un sacramento a un fiel, pero concederle ese deseo no impedía que luego llamase al presidente para pedirle una clemencia de la que éste carecía.

Castellani murió en 1981. No vio el final de la dictadura. Los intentos de desprestigiarlo son post mortem y post militares. Era un jesuita incómodo hasta para su propia orden, buen lector y gran escritor, conocedor de la historia y de la filosofía. No me sorprende que la tarea de exhumar su obra se haya emprendido en España, donde Juan Manuel de Prada se ha constituido en sabio valedor, y no en la Argentina kirchnerista.

Fuentes: de hjg.com.ar, los poemas dedicados a Santo Tomás y a Dios;el poema Jauja lo hemos tomado de padreleonardocastellani.blogspot.com; la entrevista de Braceli, de www.statveritas.com.ar; el artículo del poeta y narrador -exiliado en España- Horacio Vázquez Rial lo hemos tomado de http://historia.libertaddigital.com, incluyendo finalmente, el testimonio de Juan Manuel de Prada, de You Tube.

Nota de Lisarda- Leonardo Castellani (1899-1981) fue un pensador,escritor y sacerdote argentino, cuya figura va siendo lentamente revalorizada, más allá del rezagado mundo editorial argentino.

Juan Manuel de Prada, novelista español, ha preparado y prologado una antología de textos de Castellani, bajo el título Cómo sobrevivir intelectualmente al siglo XXI (2008)